Allometry

Note the proportionately thicker bones in the elephant, an example of allometric scaling

Allometry is the study of the relationship of body size to shape,[1] anatomy, physiology and finally behaviour,[2] first outlined by Otto Snell in 1892,[3] D'Arcy Thompson in 1917[4] and Julian Huxley in 1932.[5] Allometry is a well-known study, particularly in statistical shape analysis for its theoretical developments, as well as in biology for practical applications to the differential growth rates of the parts of a living organism's body. One application is in the study of various insect species (e.g., the Hercules Beetle), where a small change in overall body size can lead to an enormous and disproportionate increase in the dimensions of appendages such as legs, antennae, or horns. The relationship between the two measured quantities is often expressed as a power law:

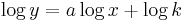

or in a logarithmic form:

or in a logarithmic form:

where  is the scaling exponent of the law. Methods for estimating this exponent from data are complicated because the usual method for fitting lines (least-squares regression) does not account for error variance in the independent variable (e.g., log body mass). Therefore, specialized methods can be used, including measurement error models and a particular kind of principal component analysis.

is the scaling exponent of the law. Methods for estimating this exponent from data are complicated because the usual method for fitting lines (least-squares regression) does not account for error variance in the independent variable (e.g., log body mass). Therefore, specialized methods can be used, including measurement error models and a particular kind of principal component analysis.

Allometry often studies shape differences in terms of ratios of the objects' dimensions. Two objects of different size but common shape will have their dimensions in the same ratio. Take, for example, a biological object that grows as it matures. Its size changes with age but the shapes are similar. Studies of ontogenetic allometry often use lizards or snakes as model organisms because they lack parental care after birth or hatching and because they exhibit a large range of body size between the juvenile and adult stage. Lizards often exhibit allometric changes during their ontogeny.[6]

In addition to studies that focus on growth, allometry also examines shape variation among individuals of a given age (and sex), which is referred to as static allometry. Comparisons of species are used to examine interspecific or evolutionary allometry (see also Phylogenetic comparative methods).

Isometric scaling and geometric similarity

Isometric scaling occurs when changes in size (during growth or over evolutionary time) do not lead to changes in proportion. An example is found in frogs - aside from a brief period during the few weeks after metamorphosis, frogs grow isometrically.[7] Therefore, a frog whose legs are as long as its body will retain that relationship throughout its life, even if the frog itself increases in size tremendously.

Isometric scaling is governed by the square-cube law. An organism which doubles in length isometrically will find that the surface area available to it will increase fourfold, while its volume and mass will increase by a factor of eight. This can present problems for organisms. In the case of above, the animal now has eight times the biologically active tissue to support, but the surface area of its respiratory organs has only increased fourfold, creating a mismatch between scaling and physical demands. Similarly, the organism in the above example now has eight times the mass to support on its legs, but the strength of its bones and muscles is dependent upon their cross-sectional area, which has only increased fourfold. Therefore, this hypothetical organism would experience twice the bone and muscle loads of its smaller version. This mismatch can be avoided either by being "overbuilt" when small or by changing proportions during growth, called allometry.

Isometric scaling is often used as a null hypothesis in scaling studies, with 'deviations from isometry' considered evidence of physiological factors forcing allometric growth.

Allometric scaling

Allometric scaling is any change that deviates from isometry. A classic example is the skeleton of mammals, which becomes much more robust and massive relative to the size of the body as the body size increases.[8] Allometry is often expressed in terms of a scaling exponent based on body mass, or body length (Snout-vent length, total length etc.). A perfectly isometrically scaling organism would see all volume-based properties change proportionally to the body mass, all surface area-based properties change with mass to the power 2/3, and all length-based properties change with mass to the 1/3 power. If, after statistical analyses, for example, a volume-based property was found to scale to mass to the 0.9 power, then this would be called "negative allometry", as the values are smaller than predicted by isometry. Conversely, if a surface area based property scales to mass to the 0.8 power, the values are higher than predicted by isometry and the organism is said to show "positive allometry". One example of positive allometry occurs among species of monitor lizards (family Varanidae), in which the limbs are relatively longer in larger-bodied species.[9]

Determining if a system is scaling with allometry

To determine whether isometry or allometry is present, an expected relationship between variables needs to be determined to compare data to. This is important in determining if the scaling relationship in a dataset deviates from an expected relationship (such as those that follow isometry). The use of tools such as dimensional analysis is very helpful in determining expected slope.[10][11][12] This ‘expected’ slope, as it is known, is essential for detecting allometry because scaling variables are comparisons to other things. Saying that mass scales with a slope of 5 in relation to length doesn’t have much meaning unless you know the isometric slope is 3, meaning in this case, the mass is increasing extremely fast. For example, different sized frogs should be able to jump the same distance according to the geometric similarity model proposed by Hill 1950[13] and interpreted by Wilson 2000,[14] but in actuality larger frogs do jump longer distances. Dimensional analysis is extremely useful for balancing units in an equation or in our case, determining expected slope. A few dimensional examples below: M-Mass L-Length V-Volume (which is also L cubed because a volume is merely length cubed)

If trying to find the expected slope for the relationship between mass and the characteristic length of an animal (see figure) you would take the units of mass (M=L3, because mass is a volume-volumes are lengths cubed) from the Y axis and divide them by the X axis (in this case L). Your expected slope in this case is 3 (L3/ L1, 3/1=3). This is the slope of a straight line, but most data gathered in science does not automatically fall neatly in a straight line, so data transformations are useful. It is also important to keep in mind what you are comparing in your data. Comparing head length to head width can yield different results than comparing to body length. Sometimes a characteristic length such as head length may scale differently to its width than body length.[15]

A common way to analyze data such as those collected in scaling is to use log-transformation. It is beneficial to transform both axes using logarithms and then perform a linear regression. This will normalize the data set and make it easier to analyze trends using the slope of the line.[16] Before analyzing data though, it is important to have a predicted slope of the line to compare your analysis to. After data are log transformed and linearly regressed. You can then use least squares regression with 95% confidence intervals or reduced major axis analysis. Sometimes the two analyses can yield different results, but often they do not. If the expected slope is outside the confidence intervals then there is allometry present. If mass in our imaginary animal scaled with a slope of 5 and this was a statistically significant value, then mass would scale very fast in this animal versus the expected value. It would scale with positive allometry. If the expected slope is 3 and in reality in a certain organism mass scaled with 1 (assuming this slope is statistically significant), then it would be negatively allometric.

Another example: Force is dependent on the cross-sectional area of muscle (CSA), which is L2. If comparing force to a length, then your expected slope is 2. Alternatively, this analysis may be accomplished with a power regression. Plot the relationship between your data onto a graph. Fit this to a power curve (depending on your stats program, this can be done multiple ways) and it will give you an equation with the form y=Zx^number. That “number” is the relationship between your data points. The downside to this form of analysis is that it makes it a little more difficult to do statistical analyses.

Physiological scaling

Many physiological and biochemical processes (such as heart rate, respiration rate or the maximum reproduction rate) show scaling, mostly associated with the ratio between surface area and mass (or volume) of the animal. The metabolic rate of an individual animal is also subject to scaling.

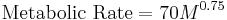

Metabolic rate and body mass

In plotting an animal's basal metabolic rate (BMR) against the animal's own body mass, a logarithmic straight line is obtained. Overall metabolic rate in animals is generally accepted to show negative allometry, scaling to mass to a power ~0.75, known as Kleiber's law, 1932. This means that larger-bodied species (e.g., elephants) have lower mass-specific metabolic rates and lower heart rates, as compared with smaller-bodied species (e.g., mice), this straight line is known as the "mouse to elephant curve".

Max Kleiber contributed the following allometric equation for relating the BMR to the body mass of an animal.[17] Statistical analysis of the intercept did not vary from 70 and the slope was not varied from 0.75, thus:

where  is body mass, and metabolic rate is measured in watts or Kcal per day.

is body mass, and metabolic rate is measured in watts or Kcal per day.

Consequently the body mass itself can explain the majority of the variation in the BMR. In removing the concept of body mass, the taxonomy of the animal assumes a major role in the scaling of the BMR. The further speculation that environmental conditions play a role in BMR can only be properly investigated once the role of taxonomy is established. The challenge with this lies in the fact that a shared environment also indicates a common evolutionary history and thus a close taxonomic relationship. There are strides currently in research to overcome these hurdles, for example an analysis in muroid rodents,[17] the mouse, hamster, and vole type, took into account taxonomy. Results revealed the hamster (warm dry habitat) had lowest BMR and the mouse (warm wet dense habitat) had the highest BMR. Larger organs could explain the high BMR groups, along with their higher daily energy needs. Analyses such as this demonstrate the physiological adaptations to environmental changes that animals undergo.

Energy metabolism is subjected to the scaling of an animal and can be overcome by an individual's body design. The metabolic scope for an animal is the ratio of resting and maximum rate of metabolism for that particular species as determined by oxygen consumption. Oxygen consumption Vo2 and maximum oxygen consumption VO2 max. Oxygen consumption in species that differ in body size and organ system dimensions show a similarity in their charted Vo2 distributions indicating that despite the complexity in their systems, there is a power law dependence of similarity; therefore, universal patterns are observed in diverse animal taxonomy.[18]

Across a broad range of species, allometric relations are not necessarily linear on a log-log scale. For example, the maximal running speeds of mammals show a complicated relationship with body mass, and the fastest sprinters are of intermediate body size. [19] [20]

Allometric muscle characteristics

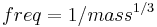

The muscle characteristics of animals are similar in a wide range of animal sizes, though muscle sizes and shapes can and often do vary depending on environmental constraints placed on them. The muscle tissue itself maintains its contractile characteristics and does not vary depending on the size of the animal. Physiological scaling in muscles affects the number of muscle fibers and their intrinsic speed to determine the maximum power and efficiency of movement in a given animal. The speed of muscle recruitment varies roughly in inverse proportion to the cube root of the animal’s weight, such as the intrinsic frequency of the sparrow’s flight muscle compared to that of a stork’s.

For inter-species allometric relations related to such ecological variables as maximal reproduction rate, attempts have been made to explain scaling within the context of dynamic energy budget theory and the metabolic theory of ecology. However, such ideas have been less successful.

Allometry of legged locomotion

Methods of study

Allometry has been used to study patterns in locomotive principles across a broad range of species.[21][22][23][24] Such research has been done in pursuit of a better understanding of animal locomotion, including the factors that different gaits seek to optimize.[24] Allometric trends observed in extant animals have even been combined with evolutionary algorithms to form realistic hypotheses concerning the locomotive patterns of extinct species.[23] These studies have been made possible by the remarkable similarities among disparate species’ locomotive kinematics and dynamics, “despite differences in morphology and size”.[21]

Allometric study of locomotion involves the analysis of the relative sizes, masses, and limb structures of similarly shaped animals and how these features affect their movements at different speeds.[24] Patterns are identified based on dimensionless Froude numbers, which incorporate measures of animals’ leg lengths, speed or stride frequency, and weight.[23][24]

Alexander incorporates Froude-number analysis into his “dynamic similarity hypothesis” of gait patterns. Dynamically similar gaits are those between which there are constant coefficients that can relate linear dimensions, time intervals, and forces. In other words, given a mathematical description of gait A and these three coefficients, one could produce gait B, and vice versa. The hypothesis itself is as follows: “animals of different sizes tend to move in dynamically similar fashion whenever the ratio of their speed allows it.” While the dynamic similarity hypothesis may not be a truly unifying principle of animal gait patterns, it is a remarkably accurate heuristic.[24]

It has also been shown that living organisms of all shapes and sizes utilize spring mechanisms in their locomotive systems, probably in order to minimize the energy cost of locomotion.[25] The allometric study of these systems has fostered a better understanding of why spring mechanisms are so common,[25] how limb compliance varies with body size and speed,[21] and how these mechanisms affect general limb kinematics and dynamics.[22]

Principles of legged locomotion identified through allometry

- Alexander found that animals of different sizes and masses traveling with the same Froude number consistently exhibit similar gait patterns.[24]

- Duty factors—percentages of a stride during which a foot maintains contact with the ground—remain relatively constant for different animals moving with the same Froude number.[24]

- The dynamic similarity hypothesis states that “animals of different sizes tend to move in dynamically similar fashion whenever the ratio of their speed allows it”.[24]

- Body mass has even more of an effect than speed on limb dynamics.[22]

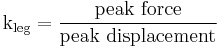

- Leg stiffness,

, is proportional to

, is proportional to  , where

, where  is body mass.[22]

is body mass.[22] - Peak force experienced throughout a stride is proportional to

.[22]

.[22] - The amount by which a leg shortens during a stride (i.e. it's peak displacement) is proportional to

.[22]

.[22] - The angle swept by a leg during a stride is proportional to

.[22]

.[22] - The mass-specific work rate of a limb is proportional to

.[22]

.[22]

Allometric scaling in fluid locomotion

The mass/density of organism has a large effect on organisms locomotion through a fluid. For example tiny organisms use flagella and can effectively move through a fluid it is suspended in. Then on the other scale a Blue Whale that is much more massive and dense in comparison with the viscosity of the fluid, compared to a bacterium in the same medium. The way in which the fluid interacts with the external boundaries of the organism is important with locomotion through the fluid. For streamlined swimmers the resistance or drag determines the performance of the organism. This drag or resistance can be seen in two distinct flow patterns. There is Laminar Flow where the fluid is relatively uninterrupted after the organism moves through it. Turbulent flow is the opposite, where the fluid moves roughly around an organisms that creates vortices that absorb energy from the propulsion or momentum of the organism. Scaling also effects locomotion through a fluid because of the energy needed to propel an organism and to keep up velocity through momentum. The rate of oxygen consumption per gram body size decreases consistently with increasing body size.[26] (Knut Schmidt-Nielson 2004)

In general, smaller, more streamlined organisms create Laminar Flow (R<0.5x106), whereas larger, less streamlined organisms produce Turbulent Flow(R>2.0x106).[13] Also increase in velocity(V), increases turbulence, which can be proved using the Reynolds equation. In nature however organisms such as a 6‘-6” dolphin moving at 15 knots does not have the appropriate Reynolds numbers for Laminar flow R=107, but exhibit it in nature. Mr. G.A Steven observed and documented dolphins moving at 15 knots alongside his ship leaving a single trail of light when phosphorescent activity in the sea was high. The factors that contribute are:

-Surface area of the organism and its effect on the fluid in which the organism lives is very important in determining the parameters of locomotion.

-The Velocity of an organism through fluid changes the dynamic of the flow around that organism and as velocity increases the shape of the organism becomes more important for laminar flow.

-Density and Viscosity of fluid.

- Length of the organism is factored into the equation because the surface area of just the front 2/3 of the organism has an effect on the drag

The resistance to the motion of an approximately stream-lined solid through a fluid can be expressed by the formula: Cfρ(total surface)V2/2 [13]

V = velocity

ρ = density of fluid

Cf = 1.33R-1 (laminar flow) R= Reynolds number

Reynolds number [R]=VL/ν

V = velocity

L = Axial length of organism

ν = kinematic viscosity (viscosity/density)

Notable Reynolds numbers:

R<0.5x106 = Laminar Flow Threshold

R>2.0x106 = Turbulent Flow Threshold

Scaling also has an effect on the performance of organisms in fluid. This is extremely important for marine mammals and other marine organisms that rely on atmospheric oxygen to survive and carry out respiration. This can effect how fast an organism can propel itself efficiently and more importantly how long it can dive, or how long and how deep an organism can stay underwater. Heart mass and lung volume are important in determining how scaling can effect metabolic function and efficiency. Aquatic mammals, like other mammals, have the same size heart proportional to their bodies. Mammals have a heart that is about 0.6% of the total body mass across the board from a small mouse to a large Blue Whale. It can be expressed as: Heart Weight =0.006Mb1.0. Where Mb is the body mass of the individual. (Knut Scmidt-Nielson 1997) Lung Volume is also directly related to body mass in mammals (slope = 1.02). The lung has a volume of 63 ml for every kg of body mass. In addition, the tidal volume at rest in an individual is 1/10th the lung volume. Also respiration costs with respect to oxygen consumption is scaled in the order of Mb.75. (Knut Scmidt-Nielson 1997) This shows that mammals, regardless of size have the same size respiratory and cardiovascular systems and it turn have the same amount of blood. About 5.5% of body mass. This means that for a similarly designed marine mammals, the larger the individual the more efficiently they can travel compared to a smaller individual. It takes the same effort to move one body length whether the individual is one meter or ten meters. This can explain why large whales can migrate far distance in the oceans and not stop for rest. It is metabolically less expensive to be larger in body size. (Knut Scmidt-Nielson 1997) This goes for terrestrial and flying animals as well. In fact, for an organism to move any distance, regardless of type from elephants to centipedes, smaller animals consume more oxygen per unit body mass than larger. This metabolic advantage that larger animals have make it possible for larger marine mammals to dive for longer durations of time than their smaller counterparts. The fact that the heart rate is lower means that larger animals can carry more blood, which carries more oxygen. Then in conjuncture with the fact that mammals reparation costs scales in the order of Mb.75 shows how an advantage can be had in having a larger body mass. More simply, a larger whale can hold more oxygen and at the same time demand less metabolically than a smaller whale. Traveling long distances and deep dives are a combination of good stamina and also moving an efficient speed and in an efficient way to create laminar flow, reducing drag and turbulence. In sea water as the fluid, it traveling long distances in large mammals, such as whales, is facilitated by the fact that they are neutrally buoyant and have their mass completely supported by the density of the sea water. On land animals have to expend a portion of their energy during locomotion to fight the effects of gravity. It should be mentioned that flying organisms such as birds are also considered moving through a fluid. In scaling birds of similar shape it has also been seen that larger individuals have less metabolic cost per kg than smaller species. This would be expected because it holds true for every other form of animal. Birds also have a variance in wing beat frequency. Even with the compensation of larger wings per unit body mass, larger birds also have a slower wing beat frequency. This allows larger birds to fly at higher altitude, longer distances, and at faster absolute speeds than smaller birds. Because of the dynamics of lift-based locomotion and the fluid dynamics, birds have a U shaped curve for metabolic cost and velocity. Because flight, in air as the fluid, is metabolically more costly at the lowest and the highest velocities. On the other end small organisms such a insects can make gain advantage from the viscosity of the fluid (air) that they are moving in. A wing-beat timed perfectly can effectively uptake energy from the previous stroke. (Dickinson 2000) This form of wake capture allows an organism to recycle energy from the fluid or vortices within that fluid created by the organism itself. This same sort of wake capture occurs in aquatic organisms as well, and for organisms of all sizes. This dynamic of fluid locomotion allows smaller organisms gain advantage because the effect on them from the fluid is much greater because of there relatively smaller size.

Allometric engineering

Allometric engineering is a method for manipulating allometric relationships within or among groups.[29]

Examples

Some examples of allometric laws:

- Kleiber's law, metabolic rate

is proportional to body mass

is proportional to body mass  raised to the

raised to the  power:

power:

- breathing and heart rate

are both proportional to body mass

are both proportional to body mass  raised to the

raised to the  power:

power:

- mass transfer contact area

and body mass

and body mass  :

:

- the proportionality between the optimal cruising speed

of flying bodies (insects, birds, airplanes) and body mass

of flying bodies (insects, birds, airplanes) and body mass  raised to the power

raised to the power  :

:

Determinants of size in different species

Many factors go into the determination of body mass and size for a given animal. These factors often affect body size on an evolutionary scale, but conditions such as availability of food and habitat size can act much more quickly on a species. Other examples include the following:

- Physiological design

- Basic physiological design plays a role in the size of a given species. For example, animals with a closed circulatory system are larger than animals with open or no circulatory systems.[17]

- Mechanical design

- Mechanical design can also determine the maximum allowable size for a species. Animals with tubular endoskeletons tend to be larger than animals with exoskeletons or hydrostatic skeletons.[17]

- Habitat

- An animal’s habitat throughout its evolution is one of the largest determining factors in its size. On land, there is a positive correlation between body mass of the top species in the area and available land area.[30] However, there are a much greater number of “small” species in any given area. This is most likely determined by ecological conditions, evolutionary factors, and the availability of food; a small population of large predators depend on a much greater population of small prey to survive. In an aquatic environment, the largest animals can grow to have a much greater body mass than land animals where gravitational weight constraints are a factor.[13]

See also

- Biomechanics

- Comparative physiology

- Constructal theory

- Evolutionary physiology

- Metabolic theory of ecology

- Phylogenetic comparative methods

- Power law (also known as a scaling law)

- Rensch's rule

References

- ^ Christopher G. Small (1996). The Statistical Theory of Shape. Springer. p. 4. ISBN 0-387-94729-9.

- ^ http://www.pnas.org/content/98/5/2113.full

- ^ Otto Snell (1892). "Die Abhängigkeit des Hirngewichts von dem Körpergewicht und den geistigen Fähigkeiten". Arch. Psychiatr. 23 (2): 436–446. doi:10.1007/BF01843462.

- ^ D'Arcy W Thompson (1992). On Growth and Form (Canto ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521437769.

- ^ Julian S. Huxley (1972). Problems of Relative Growth (2nd ed.). New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-61114-0.

- ^ Garland, T., Jr.; P. L. Else (March 1987). "Seasonal, sexual, and individual variation in endurance and activity metabolism in lizards". Am J Physiol. 252 (3 Pt 2): R439–49. PMID 3826408. http://www.biology.ucr.edu/people/faculty/Garland/GarlEl87.pdf.

- ^ Emerson SB (September 1978). "Allometry and Jumping in Frogs: Helping the Twain to Meet". Evolution (Society for the Study of Evolution) 32 (3): 551–564. doi:10.2307/2407721. JSTOR 2407721.

- ^ Schmidt-Nielsen, K (1984). Scaling: why is animal size so important?. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-31987-0.

- ^ Christian, A.; Garland, T., Jr. (1996). "Scaling of limb proportions in monitor lizards (Squamata: Varanidae)". Journal of Herpetology (Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles) 30 (2): 219–230. doi:10.2307/1565513. JSTOR 1565513. http://www.biology.ucr.edu/people/faculty/Garland/ChriGa96.pdf.

- ^ Pennycuick, Colin J. (1992). Newton Rules Biology. the University of California: Oxford University Press. pp. 111. ISBN 0198540213, 9780198540212.

- ^ Schmidt-Nielsen, Knut (1984). Scaling: Why is Animal Size So Important?. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. pp. 237. ISBN 052131987.

- ^ Gibbings, J.C. (2011). Dimensional Analysis. New York: Springer London. pp. 297. ISBN 978-1-84996-316-9.

- ^ a b c d Hill, A.V. (April 1950). "The dimensions of animals and their muscular dynamics". Science Progress 150.

- ^ Wilson, Robbie; Craig E. Franklin, Rob S. James (2000). "ALLOMETRIC SCALING RELATIONSHIPS OF JUMPING PERFORMANCE IN THE STRIPED MARSH FROG LIMNODYNASTES PERONII". The Journal of Experimental Biology 203: 1937–1946.

- ^ Robinson, Michael; Philip Motta (2002). "Patterns of growth and the effects of scale on the feeding kinematics of the nurse shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum)". Journal of Zoology, London 256: 449–462.

- ^ O'Hara, R.B.; Kotze, D.J. (2010). "Do Not Log Transform Count Data". Nature Preceedings.

- ^ a b c d Willmer, Pat (2009). Environmental Physiology of Animals. Wiley-Blackwell.

- ^ Labra, F.; P. Marquet, F. Bozinovic (June 2007). "Scaling Metabolic Rate Fluctuations". PNAS.

- ^ Garland, T., Jr. (1983). "The relation between maximal running speed and body mass in terrestrial mammals". Journal of Zoology, London 199 (2): 157–170. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1983.tb02087.x. http://www.biology.ucr.edu/people/faculty/Garland/Garl1983_JZL.pdf.

- ^ Chappell, R. (1989). "Fitting bent lines to data, with applications to allometry". Journal of Theoretical Biology 138 (2): 235–256. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(89)80141-9. PMID 2607772.

- ^ a b c Daley, Monica A.; Usherwood, James R. (2010). "Two explanations for the compliant running paradox: reduced work of bouncing viscera and increased stability in uneven terrain". Biology Letters 6: 418–421. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.0175.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Farley, Claire T.; Glasheen, James; McMahon, Thomas A. (1993). "Running springs: speed and animal size". The Journal of Experimental Biology 185: 71–86.

- ^ a b c Sellers, William Irving; Manning, Phillip Lars (2007). "Estimating dinosaur maximum running speeds using evolutionary robotics". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 247: 2711–2716. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0846.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Alexander, R. McN. (1984). "The gaits of bipedal and quadrupedal animals". The International Journal of Robotics Research 3 (2): 49–59.

- ^ a b Roberts, Thomas J.; Azizi, Emanuel (2011). "Fleximble mechanisms: the diverse roles of biological springs in vertebrate movement". The Journal of Experimental Biology 214: 353–361. doi:10.1242/jeb.038588.

- ^ Schmidt-Nielsen, Knut (1997). Animal physiology adaptation and environment (5. ed. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 0521570980.

- ^ Dickinson, Michael H.; Farley, Claire T.; Full, M; Koehl, R; Kram, Rodger; Lehman, Steven. How Animals Move: An Integrative View. Science Vol. 288, 100-106 (April 7, 2000)

- ^ Knut Schmidt-Nielson. Animal Physiology, adaptation and envronment. 5th edition.Cambridge University Press 1997.

- ^ Sinervo, B. and Huey, R. (1990). "Allometric Engineering: An Experimental Test of the Causes of Interpopulational Differences in Performance". Science 248 (4959): 1106–1109. doi:10.1126/science.248.4959.1106. http://faculty.washington.edu/hueyrb/pdfs/SinervoScience1.pdf.

- ^ Burness, G. P.; Diamond, Jared; Flannery, Timothy (2001). "Dinosaurs, dragons, and dwarfs: The evolution of maximal body size". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98 (25): 14518–14523. doi:10.1073/pnas.251548698.

Further reading

- Calder, W. A. (1984). Size, function and life history. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-81070-8.

- McMahon, T. A. and J. T. Bonner (1983). On Size and Life. New York: Scientific American Library. ISBN 0-7167-5000-7.

- Niklas, K. J. (1994). Plant allometry: The scaling of form and process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-58081-4.

- Peters, R. H. (1983). The ecological implications of body size. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-28886-X.

- Reiss, M. J. (1989). The allometry of growth and reproduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42358-9.

- Schmidt-Nielsen, K. (1984). Scaling: why is animal size so important?. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-31987-0.

- Samaras, Thomas T. (2007). Human body size and the laws of scaling: physiological, performance, growth, longevity and ecological ramifications. Nova Publishers. ISBN 1-60021-408-8. book entry at Google Books

External links

- FDA Guidance for Estimating Human Equivalent Dose (For "first in human" clinical trials of new drugs)

![V_{opt} \sim 30 \cdot M^{\frac 1 6} [m \cdot s^{-1}]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7712ac54fbd60b50a43cb82f8c92f3c5.png)